THE FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY-- The Field Museum of Natural History’s ‘Opening the Vaults: Wonders of the 1893 World’s Fair’ showcases an inspiring array of artifacts which became part of the Museum’s collection in its early years both as a museum and as one of the world’s leading natural history research institutions. The exhibition celebrates in these artifacts two milestones: the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the formative years of the Columbian Museum of Chicago (which later became the Field Museum).

Designed by its American hosts to spotlight the United States’ industrial and territorial achievements on the four hundredth anniversary of the journey of Columbus to the New World, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition signaled the entrée of a new world power in North America. Embodying the spirit of emergent American exceptionalism, the Columbian Exposition surpassed previous expositions of the Victorian period in scale and splendor. In addition to the tens of buildings devoted to the American project, many foreign nations sent delegations to construct their own exhibitions on the grounds at Jackson Park in Chicago.

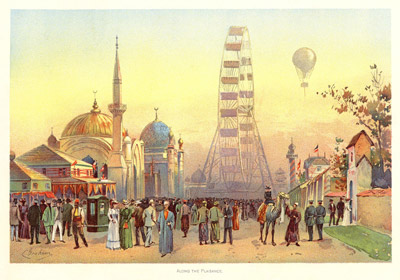

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was undoubtedly one of the most magnificent spectacles of the nineteenth century. With 65,000 exhibits in more than 200 buildings spanning 600 acres, the ‘White City’ was a breathtaking sight to behold. A $47 million feat of architecture and of electricity, the Columbian Exposition transformed not only the city of Chicago, but also set the tone for future advancements in science and industry. 27 million people attended and were exposed to the most progressive thinking and cutting-edge technology of the era.

Sadly, the Field’s ‘Opening the Vaults’ does little to capture the magnitude and historical impact of this monumental event. Though the exhibition is nonetheless an estimable attempt to display historically important objects (and indeed, the beautifully restored museum display cases are one of its best features) and the curators are to be commended for their willingness to engage critical questions, it is yet fraught with problems.

The exhibition begins on solid footing with an introduction accompanied by an array of artifacts – entry tickets, a logbook, and a piece of machinery whose purpose remains unknown (the exhibition asks visitors to contact the curators if they have any clue to the item’s original use). An enormous Japanese earthen tea jar and zoological skeleton, however, lack context in an introduction which, overall, falls short of conveying to visitors what the Columbian Exposition meant to Chicago and perhaps more importantly, what the chance to attend the Columbian Exposition meant to fairgoers who came from destinations near and far to enjoy what was regarded as a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

The exhibition is at its best in displays focusing on the elaborate botanical and geological concessions which were indeed a highlight at the Exposition itself. Exhibition text notes that though the modern day Field Museum’s mission is to promote conservation and sustainability, the institution at its founding in 1893 embodied the Victorian spirit of industry. Magnificent and costly displays showcased raw mineral products, celebrating mining and forestry, and demonstrating a multiplicity of commercial and industrial uses for natural products. Hats made of taxidermal birds, gloves made from sea sponges, and lace from tree bark are all excellent examples of how Victorian era vendors peddled their wares to fairgoers while industrial booths created a trade fair of sorts for oil and mining companies.

The final section of ‘Opening the Vaults’; a series of displays devoted to the anthropological aspects of the Columbian Exposition, trains a critical eye on the ethics of ethnographic showcase in the Victorian period. World’s fairs of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries provided an international forum through which power and culture relations were played out in a constructed public environment. The Columbian Exposition of 1893 was no exception. The event was, we learn, ultimately the site of appropriation, racialized power hierarchies, colonial construction, and orientalism in which the familiar West was contrasted with the alterity of the East; organized along colonial and later post-colonial lines. In this assessment, the curators are exactly right. The Columbian Exposition arrived at the height of the age of empire; colonial powers were engaged in extractive agendas in Africa and Asia, further accelerating the race to industrialization and deepening an already fortified racial hierarchy. The world in 1893 was one of entrenched inequality, not only for citizens of non-Western nations but also for women, non-whites, immigrants, laborers, and the disabled, among others, in America.

What is troubling, however, is that the curators go beyond historical analysis, applying a modern standard of ethics to judge the institutions of our nation’s past. In so doing, they miss the point that the 1893 Columbian Exposition, though undoubtedly a product of its time, did lay the foundations for the development of modern science and progressive thinking which came later in the 20th century. The development of nationalism, a process occurring largely in tandem with industrialization, saw the emergence of new jockeying on the international stage for access to the benefits of globalism and ‘progress’. Exhibitions in the late nineteenth century not only served as entertainment, but also as forums for intellectual exchange and stages on which new conceptions of international community were vetted. Therefore, despite the embrace of orientalist colonial hierarchies along the Columbian Exposition’s Midway Plaisance, the exhibition also served as the site of constructive political and cultural identity production.

Perhaps one of the best examples of social progress at the Columbian Exposition – which sadly was not mentioned at all in ‘Opening the Vaults’ – was the groundbreaking Japanese national concession on the ‘Wooded Isle,’ a location considered to be prime real estate in the White City. On invitation from the Fair’s organizers, the Japanese Meiji government sent a delegation from Tokyo at unprecedented expense to represent the nation of Japan in Chicago. A curatorial team under the direction of renowned art historian and nationalist Okakura Kakuzō developed the Japanese exhibition as a means of promulgating national identity through cultural artifacts. It was Japan’s project at the fair, filtered through Okakura’s own political vision, that the Japanese national agenda made its way into an underlying political discourse at Chicago as a nationally-constructed identity was reified among an international audience.

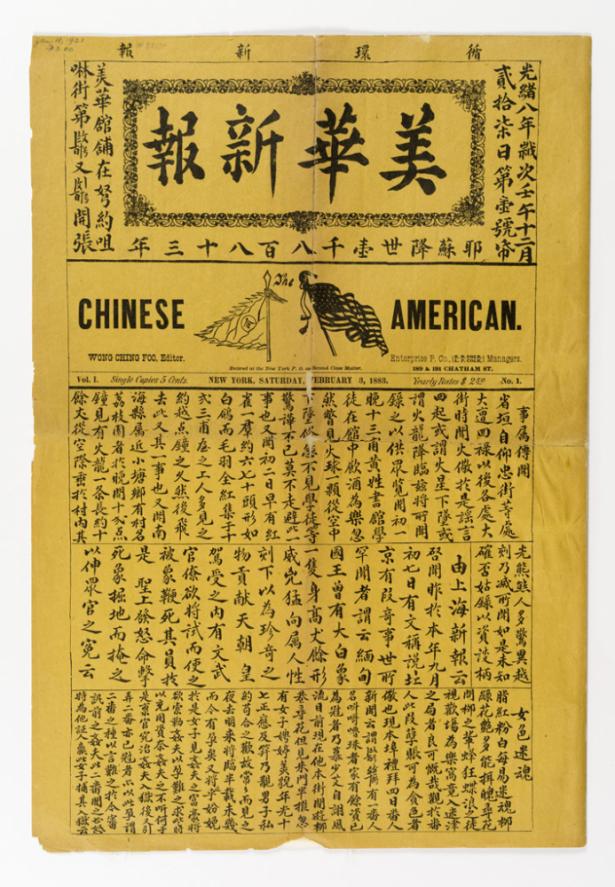

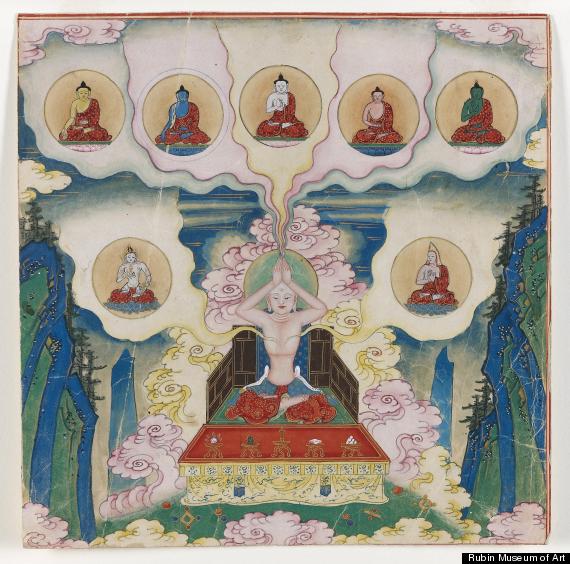

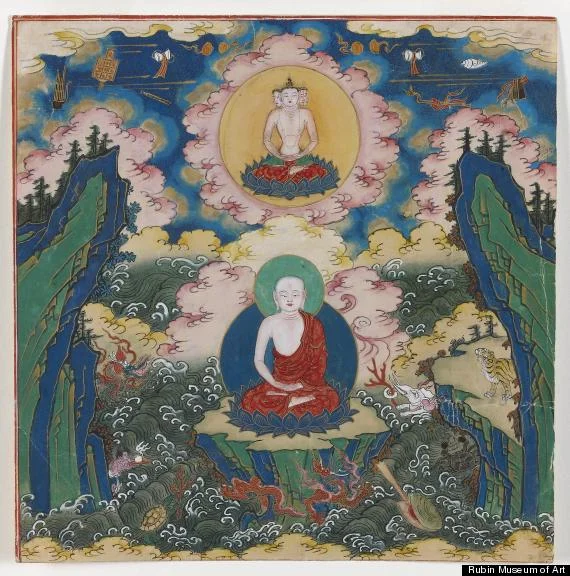

The Japanese concession at the 1893 Columbian Exposition put Japan on equal footing with the United States and its counterparts in Western Europe. It was an example in which a non-Western nation was not only invited to build its own exhibit, but it was given free rein to communicate to fairgoers a message about the nation – one in which Japan is portrayed as sophisticated, developed, and a political equal to its Western counterparts. Objects from the Japanese concession of 1893 exist within the Field Museum’s collection and had the curators chosen to include them, it could have provided a crucial counterpoint to the nuanced and complex issue of ethnography at the Columbian Exposition. Also not mentioned was the ground-breaking World’s Congress of Religions, a conference organized as part of the 1893 Fair which is now recognized as the first instance of formal interreligious dialogue in history.

Unfortunately, ‘Opening the Vaults,’ is something of a missed opportunity. With such a rich collection of artifacts from this period, however, the Field Museum is in no way diminished by what was simply a misstep in celebrating the institution’s founding moment. In fact, even beyond the dedicated exhibition, hundreds of objects dating to the 1893 Columbian Exposition are peppered throughout the Field’s extensive permanent exhibition spaces; a complete list of which can be obtained at the information booth in Stanley Field Hall.