THE BRITISH MUSEUM-- The Japanese erotic art form known as ‘shunga’ has for many centuries been part of the Japanese artistic tradition. Produced in Japan between 1600 and 1900, shunga were created by artists of the ukiyo-e or ‘floating world’ school. These colorful woodblock prints depicted sexuality in many idealized and often imaginative forms. Shunga were appreciated by individuals at all strata of society and, though banned for much of the 20th century, enjoyed widespread circulation at the heyday of the style during the Edo period (1603-1867).

The British Museum’s exhibition Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art explores many facets of the style, from artistic production to the many unsuccessful attempts by various governmental entities to regulate the dissemination of shunga artworks. A monumental collection of some of the most famous works of shunga, the exhibition reinvigorates the discourse on the role of erotica in aesthetic consumption through history and suggests how the form may have influenced later Japanese artistic styles such as manga and anime.

The origins of shunga can be traced to the Heian period (794-1185) in Japan when the style developed in the form of narrative erotic handscrolls. At its inception, shunga was consumed only by the courtier class and depictions of erotic acts were constrained chiefly to monks and courtiers. The oldest examples of shunga in the exhibition date to this earlier period when scrolls were hand-painted after the Kanō school.

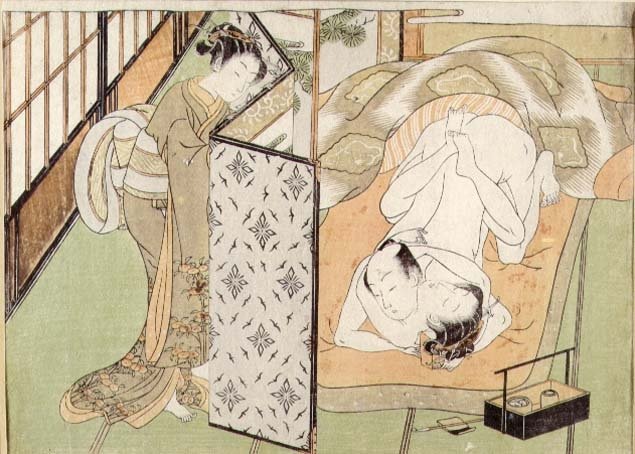

With the advent of woodblock printing by 1600, however, the production of shunga erupted. Widespread publishing guilds circulated shunga alongside an array of other literature. The production of small erotic books known as kōshokubon eventually drew sanction from the Tokugawa shogunate in 1661 when the first attempts were made to ban some forms of shunga. More ambitious sanctions followed a hundred years later with the Kansei Reforms of the 1790s. Even still, the art of shunga continued to flourish. On view in the exhibition, the 1785 Handscroll for the sleeve by Torii Kiyonaga depicts a series of twelve erotic couplings in a portable format that could easily be tucked into the deep sleeve of a kimono.

Among the highlights of the collection are Kitagawa Utamaro’s Lovers in an upstairs room from the series Uta makura (‘Poem of the Pillow’), circa 1788. In what is recognized as one of the greatest masterpieces of erotic art in the ukiyo-e canon, a couple embraces under a transparent sheet, the bright white of their skin shown through the sensuous drapery of their clothing. Utamaro was famed for his sensual imagery, often forgoing more direct depictions of sex in favor of an exquisite intimacy and sensuality. In fact, the depiction of both male and female pleasure was characteristic of the shunga style not only in Utamaro’s works but also in that his contemporaries.

Perhaps the most widely-known ukiyo-e artist of the period, the great Katsushika Hokusai made several significant contributions to the shunga form. In the artist’s remarkable Adonis Flower Series (c.1822-1823), scrolling text surrounding images of couples engaged in blissful lovemaking give viewers insight into their intimate and often cheeky conversation. Hokusai’s most famous work of shunga, however, is The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814) – also on view in the exhibition. Depicting a zoophilic encounter between a young ama diver and two octopuses, the image was long misinterpreted as a rape scene by nineteenth century Western scholars.

Japan’s long history of isolationism, or sakoku – a policy formally in effect until the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853 – may have in part contributed to the proliferation of erotic art forms like shunga that would not have been possible in nations touched by the influence of European mores. Despite what was often explicit subject matter, works of shunga were not considered pornographic or shameful; rather, they were enjoyed by male and female viewers alike. Such a practice would have been unthinkable in Europe at the time.

Herein lies perhaps the most interesting aspect of Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art. Even in contemporary times, Western viewers are hardly accustomed to viewing such explicit imagery; in fact, the topic of sexuality rarely makes its way into history and art museums despite progressive scholarly views on the subject. Yet, in Shunga we Western viewers are permitted to, for a moment, see these images not as pornography but as Japanese viewers during the Edo period may have seen them; as works of art and amusement.