MUSEUM OF MODERN ART-- ‘Gaugin: Metamorphoses,’ now on view at the Museum of Modern Art, is no typical art exhibition; rather, it is an enlightened call to fundamentally reframe our understanding of the famed French post-Impressionist, his artistic practice, and his times. That intellectual shift, so excellently crafted by the curators at MoMA, is something not often seen in the Impressionist wing of contemporary museums. The exhibition focuses on the latter years of Paul Gauguin’s career as the artist sought refuge from the modern mores of ‘civilized’ Europe in Tahiti – a land whose culture he romanticized as an exotic and primitive utopia. His works from this period – the more well-known figural Tahitian scenes in tandem with his much darker Symbolist sketches – together paint a picture of a man struggling to reconcile nonconformist ideas about spirituality, death, and sexual freedom.

Paul Gauguin, master post-Impressionist painter active in the second half of the nineteenth century, is known for his unique use of color, Synthetist style, experimentation with Cloisonnism, and pastoral subject matter. Gauguin was born in Paris in 1848, but spent much of his childhood in Lima, Peru – an experience he would later site as influential in his artistic practice. Associated with the Pont Aven School in his earlier years as a full-time painter, Gauguin began to experiment in his imagery with the allure of an idyllic rural life.

The exhibition, which houses 170 works, explores Gauguin’s perception of alterity and paradise as it was reified in his artwork. As we learn in walking through its galleries, the sexualized Tahitian utopia of Gauguin’s imagination had, by the time of his arrival, already been marred by European influence. Though the idealized primitivism of the culture he found in Tahiti is showcased in many of Gauguin’s more familiar paintings of tanned native beauties, his explorations in other media – woodcut prints, ceramics, woodcarving, transfer drawings – are what cause us to linger. These works, in their darkness and emotionality reflect a more troubled, nuanced artist in Gauguin.

We learn that it was part of Gauguin’s practice to reinvent and recombine images across mediums, allowing them to metamorphose, adapt, and index new meanings. It is this practice – one from which the exhibition takes its name – through which the artist refracted the artistic traditions of other cultures. In so doing, Gauguin became one of the first European artists to give serious credence to the art of non-Western civilizations.

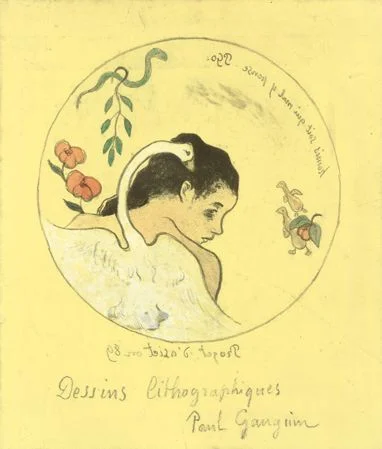

A focal point of ‘Metamorphoses,’ three print series created between 1889 and Gauguin’s death in 1903 serve as compendia of the artist’s processural journey. The earliest among these, the 1889 Volpini Suite is a set of eleven zincographs which revisit Gauguin’s travels in Brittany, Arles, and Martinique in the formative stages of his quest for a land untouched by the standards of modern Europe. Scrolling text wound carefully through the images as well as markedly unconventional compositions make clear the departure of Volpini from Gauguin’s other work during this time. A highlight of the series, a print entitled ‘Dramas of the Sea: Descent into the Maelstrom’ is especially powerful. In the ark-like image, a sailor grips at the edge of his vessel in the midst of a perilous storm at sea, perhaps a nod to the emotional journey of the artist himself.

Gauguin’s unfinished Noa Noa (“fragrant scent”) series, compiled upon his return to France in 1894, was meant to pair text with images borrowed from Gauguin’s treasured Tahitian work in an effort to make the series more accessible to the fastidious tastes of a nineteenth century Parisian audience. "All the joys—animal and human—of a free life are mine," He wrote. "I have escaped everything that is artificial, conventional, customary. I am entering into the truth, into nature." Noa Noa is a dark masterpiece, showcasing local Tahitian folklore and symbology as it had found its way into Gauguin’s opus through the years. Portraits of evil spirits, the Devil, and a rendering of a folkloric genesis narrative together with more classical bucolic imagery make the series truly a masterwork of retrospection.

‘Gauguin: Metamorphoses’ has repositioned the artist within the modern canon. It encourages us to appreciate Gauguin for his evolved approach to his own artistic practice, revisiting and reinventing imagery in different mediums, experimenting with novel textural and geometric usages, and borrowing the art forms of non-Western cultures. Yet despite its scope and intellectual audacity, the message of this exhibition is subtle; demonstrative rather than didactic. ‘Metamorphoses’ raises the bar for contemporary art museums and encourages viewers to challenge our preconceptions of the classics. It is, in a word, essential.