THE NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY--

Chinese-American archetypes are peppered throughout the national imagination. From Arnold Genthe’s century-old Chinatown photographs to the familiar literary caricature of Lee Chong in Steinbeck’s Cannery Row, clichéd imagery of Chinese Americans through history reflects shifting political and social attitudes on a national scale. What was the experience of immigration like for the hundreds of thousands of Chinese Americans facing racism and exclusion in nineteenth and twentieth century America? What did it mean to make a life in the US? How was Chinese American identity shaped by politics and trade, exclusion and inclusion?

The exhibition ‘Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion’ is in essence a tale of identity formation as Chinese immigrants weathered the tumultuous tides of US-China relations and inconstant immigration policy from the eighteenth century to contemporary times. The New York Historical Society has created in its exhibition a complex tale of the shifting status of people of Chinese origin in American history.

The story begins in the eighteenth century as a tale of commerce. American merchants ventured to China seeking exotic spices, porcelain bone china, and silk as early as 1784 on the Empress of China, a vessel whose likeness is depicted on a decorative fan on display in the exhibition. Though the young American nation approached the Chinese with deference during this period, the later nineteenth century was characterized by animosity on the diplomatic level, first with the Opium Wars during which China was forced to relinquish its restrictions on Western imports, and later during the wave of Chinese immigration during the era of the railroads in the US.

By 1880, there were more than 100,000 Chinese living in the US. Though many were male laborers employed to build the western section of the first transcontinental railroad, women, merchants, diplomats, and students were also among the Chinese American population of the nineteenth century. Animosity toward Chinese laborers, fueled by a series of anti-Chinese riots, however, found its way into policy. On May 6, 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur; thereby constituting one of the most momentous restrictions on immigration in the nation’s history. Under this legislation, Chinese laborers (and those individuals of Chinese origin suspected of seeking work in manual labor) were prevented from entering the US; a law that remained on the books until its repeal by the Magnuson Act in 1943.

The Chinese Exclusion Act made life difficult not only for those Chinese seeking to immigrate; American citizens of Chinese descent already living in the United States were denied reentry and as a result, many families were broken up. Around the midpoint of the exhibition, the curatorial focus shifts toward the hardships faced by Chinese Americans as fallout from exclusionary immigration laws and practices.

By the early twentieth century, incoming migrants from China were routinely sent to detention barracks on Angel Island, off the coast of San Francisco. Large facsimiles of identity card documents that all Chinese Americans were required to carry – even national starlets like Anna May Wong – accompany life size reproductions of detention facility accommodations where immigrants awaited news of their status. By the early 20th century, Chinese newcomers to the US were finding ways around exclusionary laws by claiming relation to Chinese American merchant families. This practice is detailed in the exhibition’s section on ‘paper sons’; i.e. young Chinese men who sought entry to the US on purchased identity papers.

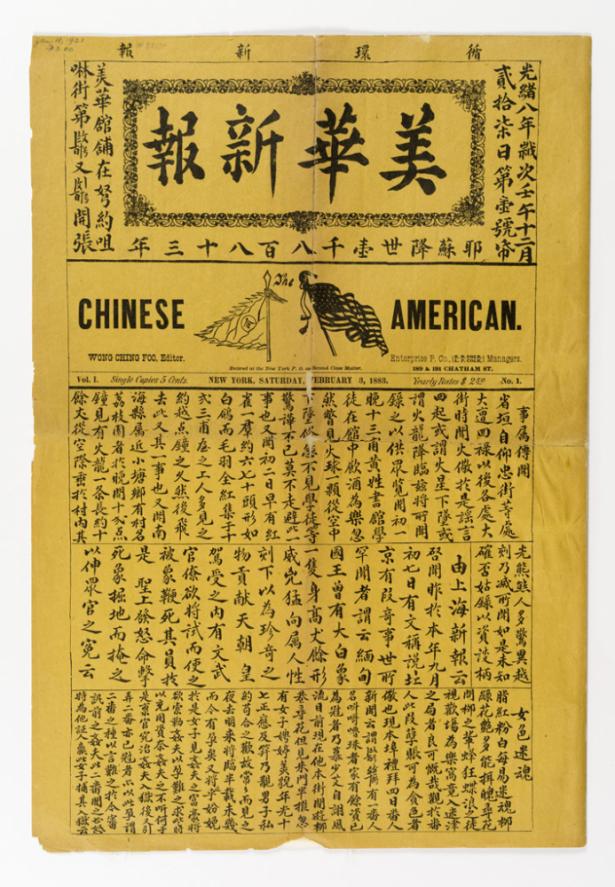

The Historical Society’s coverage of the early centuries of the Chinese in America is excellent. The exhibition showcases a variety of artifacts from a reproduction of an opium ball to mid-nineteenth century artistic depictions of Chinese theater and an 1883 newspaper article representing the first recorded usage of the term ‘Chinese American’.

Unfortunately the exhibition unravels somewhat around the post-war period. Though the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 ushered in a significant change in both US-China relations and public reception of the Chinese American population, the exhibit shifts away from a broader historical perspective in favor of personal narrative. While some may find a series of cartoons recounting the familial history of Bronx native Amy Chin and her ancestors to be endearing, it seemed to me that though the narrative spanned several decades it did so while glossing over critical detail. For example, how did the evolving relationship between Maoist China and the United States in the Nixon era affect Chinese Americans’ perception of their country of origin? How was a reaction to the Cultural Revolution and communism refracted in the formation of Chinese American identity and group consciousness?

Overall, the exhibition hits its mark, though we are left with some unanswered questions about what this centuries-old history means to Chinese Americans today. Riding the wave of the increasingly popular subject of identity politics, the New York Historical Society has created in ‘Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion’ a sound and thought-provoking starting point for productive discussion.